PPA Insights: Renewable contract structures and valuation

Author: Cyriel de Jong, KYOS Energy Analytics

PPA contract structures and valuation

The financials of renewable power and PPA contracts

This article explains what a renewable PPA contract is. Who are the buyers of such contracts and why? We also describe the main types of contracts, the contract parameters and the components that constitute the value.

What is a PPA?

A power purchase agreement (PPA) is a contractual agreement between energy buyers and sellers. It has existed for decades in the energy industry, for example between the owner of a gas-fired plant and energy buyers. The term PPA has generally been reserved for somewhat structured and often longer-term contracts, sometimes spanning even more than 20 years, not for standard electricity forwards or futures. So, PPAs are not new! What is fairly new though, and considered a booming market, is its popularity in the field of renewable generation.

Renewable PPAs, or “green” PPAs are contracts between the owner of a renewable generation asset (the electricity seller) and an off-taker (the electricity buyer). Just like “grey” PPAs, the “green” PPAs are usually signed for a long-term period between 10-20 years. One reason for the longer contract duration is that each contract requires a certain level of structuring. This requires people and money, so is not something you wish to repeat every year. For shorter durations it is cheaper to trade standard contracts in the market place, like forwards and futures.

PPAs are filling the gap

Another reason for the longer contract duration is that many PPAs are concluded at the inception of a new asset. In that phase, the PPA is the main building block to secure the future revenue stream. This is only effective if the revenue stream is secured over a long enough horizon, spanning a large part of the expected lifetime of the asset. At the same time, there is also a growing market for PPAs of existing assets, in particular assets coming out of a feed-in tariff scheme. Feed-in tariffs (abbreviated to FiT or FIT) have globally been the most popular policy measure to support renewable energy projects. Well-known examples in Europe are the EEG in Germany and the ROCS in the United Kingdom. A FiT is a government scheme which guarantees a fixed income for each MWh produced over a longer period of time. The FiT levels can vary per technology in order to accelerate innovation in specific areas. The FiT levels have decreased over time, in line with the more mature state and hence lower costs of many technologies.

This so-called tariff degression has come to a point where FiT tariffs are no longer effective. First of all, the tariffs undermine the working of a free market, and even provide perverse incentives to produce at times of oversupply and negative market prices. For the integration of solar and wind power, direct marketing the production is much more economical for the system as a whole. Secondly, the main renewable energy technologies, solar and wind, have become so mature and cost-competitive that they require limited support. As governments start to move away from subsidy schemes such as FiTs, renewable asset owners are increasingly exposed to price risks. The FiT is essentially a fixed-price PPA contract with the government. Now the time has come for the actual consumers to step in the space left behind.

Who buys a renewable PPA contract?

Natural players on the buy side of PPA contracts are the supply companies and utilities. They can integrate the electricity in their portfolio, often already comprising the direct ownership and management of other renewable assets. Utilities redistribute the power to the actual consumers, such as households and businesses. Those end-users can also decide to contract renewable energy directly from the solar park or wind farm. This is the market of so-called corporate PPAs. So far, only the largest corporate companies have entered this space. Why are corporates entering into PPAs and what are their alternatives?

Green energy options for large manufacturers

Let’s first consider the different alternatives of corporates to buy “green” energy. There are at least three: own production, green energy from a supplier and green certificates. The first possibility is to develop a renewable generation asset on-site. If the own consumption at the industrial facility or datacenter is large and stable enough, the asset may not even have to be linked to the electricity grid, thereby potentially saving network connection costs. Such “own consumption” is only possible up to a certain point, and a grid connection is always needed to cover the remaining electricity consumption. Furthermore, for corporate businesses, the development, operation and maintenance of renewable energy is not their core business and hence most likely outsourced, meaning some form of PPA contract.

The second and third alternative to a renewable PPA contract are closely connected: buying green electricity from a supplier or buying electricity in the wholesale market in combination with green certificates or guarantees of origin (GoO). With both alternatives, the exact source does not have to be a single known asset, but the supplier or certificate guarantees that it is from a certain type of green source. This can be as specific as “Bavarian solar” or “Dutch North-Sea wind” or more generally “green power from a European source”.

The on-site renewable generation asset is the most tangible you can get, while the green certificate route is the most virtual. PPA contracts sit nicely in between: the actual operation is outsourced, while there is nonetheless a direct connection to one ore more specific assets. This is what corporates increasingly prefer. Firstly, it provides direct support to new projects, allowing these to have sufficient bankability to take-off. Secondly, a direct off-take contract allows a company to be associated more directly to the asset, which raises its visibility among various stakeholders, such as customers, employees and investors. This visibility has a non-negligible value in profiling the company as sustainable.

Growth in corporate PPAs

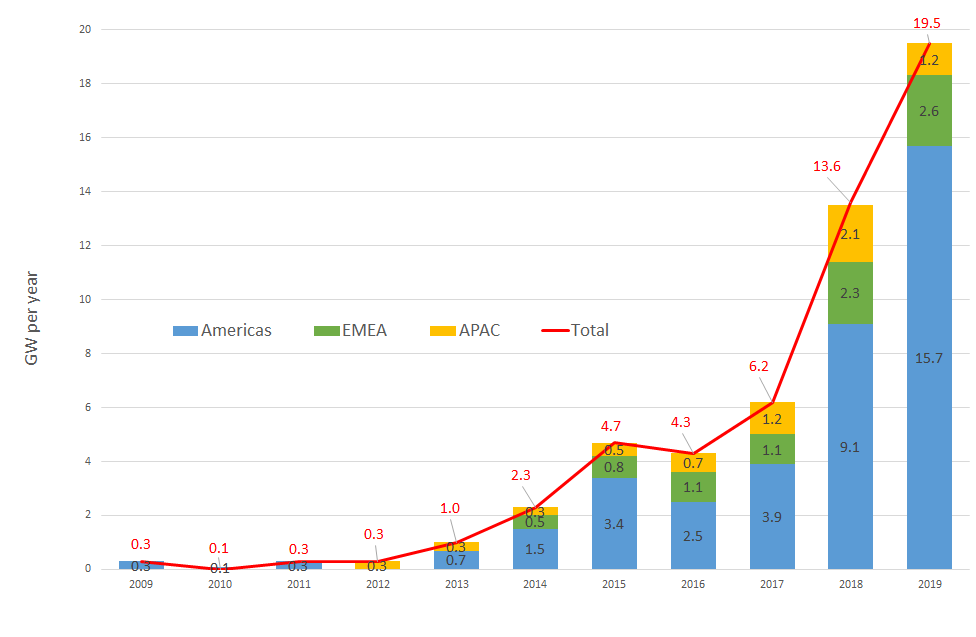

While there is limited data on PPAs bought by utilities and supply companies, the activity on the corporate PPA market is accurately tracked, for example by the journalists and researchers of Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). Their data shows that US corporations were the first movers at around 2008. That was the time when Google launched its subsidiary Google Energy to invest at a larger scale in renewable energy projects [1], mainly as a means of securing green energy to its energy guzzling data centers. According to BNEF, Google was still the top corporate buyer in 2019, with 2.7 GW signed, followed by other US tech companies Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook. The expectations are that especially Europe will see similar or even faster growth rates as the US as a result of ending FiT schemes, even though the current volume is currently much lower.

Figure 1: Global volume in corporate PPAs according to estimates of BloombergNEF. The volume is the maximum (DC) capacity of the renewable assets.

Many of the corporate PPAs in Europe have been signed by US tech companies that dominate the US market. An example is Microsoft’s purchase of a PPA from Vattenfall in 2017; the deal covers the production of the 180 MW on-shore windfarm Wieringermeer in the northwest of the Netherlands. But European companies are definitely following in the footsteps of their US rivals. Examples include the British retailer Tesco and the German car manufacturer Mercedes-Benz. Not surprisingly, the buyers in the corporate PPA market are predominantly producing consumer goods: the marketing value is larger than in the B2B market.

Physical or Virtual?

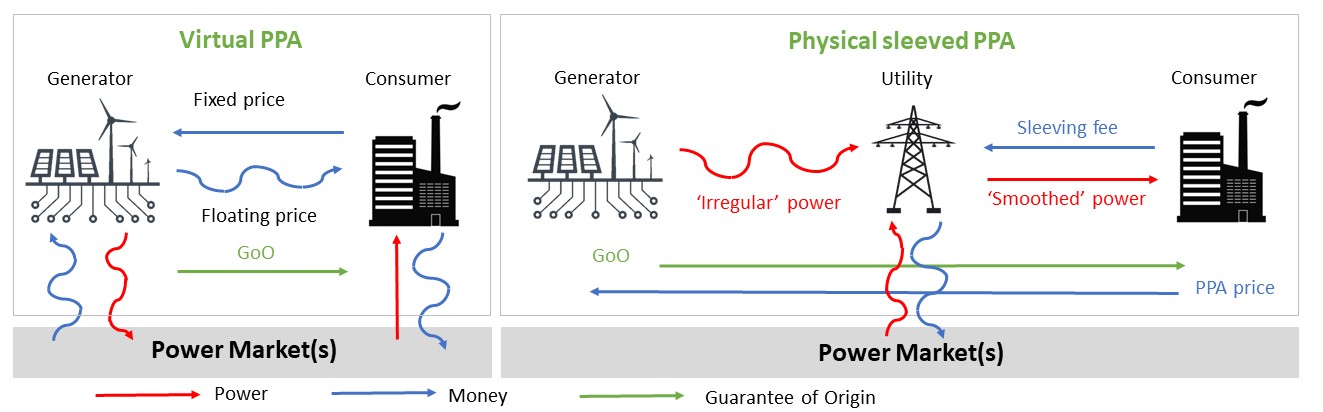

A distinction is often made between physical and virtual PPAs.

A virtual PPA is a financial contract in which the connection between the renewable generation asset and the off-taker is quite loose. For example, the off-take may be in a different country or bidding zone than the location of the asset. A virtual PPA with a fixed price is essentially a contract-for-differences: for each MWh of power produced by the generator, the buyer pays a price to the generator equal to the fixed price. In return it receives from the generator a variable (spot) price plus the Guarantees of Origin (GoOs). Separate to this virtual PPA contract, the generator can sell its power to the market, and the buyer can source its power from the market (or a supply company) as well.

In a physical PPA structure, the generator and the off-taker must be on the same grid. A physical PPA is generally sleeved by a utility, meaning that a utility is in between the generator and the off-taker to deliver the actual electricity, especially to manage the volume fluctuations. For this activity, the utility receives a sleeving fee.

A natural role for a utility is to manage volume fluctuations of an energy portfolio, whereas this is not a natural role for a corporate consumer. Unless the generator is a utility itself, many physical corporate PPAs have a utility to “sleeve” the volumes from generator to corporate consumer. In such a sleeved corporate PPA, the utility takes care of the short-term forecasting of the production, the daily nominations to the network operator and the short-term balancing, in return for a sleeving fee. In fact, the utility transforms the irregular flow of the renewable generator into a smoother flow for the consumer. With sufficient scale in such operations, a utility benefits from economies of scale and diversification to be of real added value.

Components of PPA value

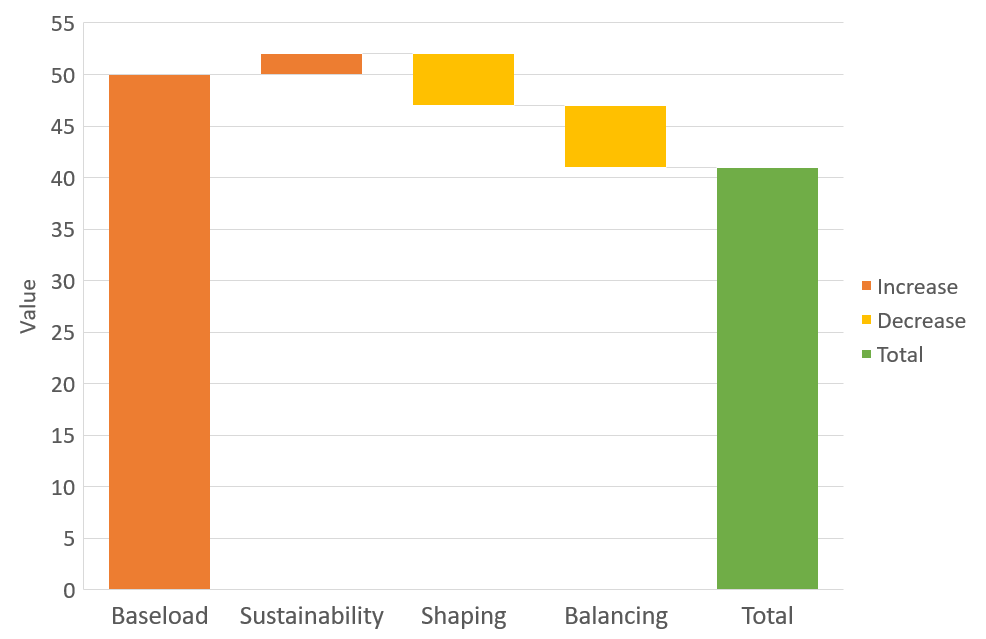

This brings us to the different value components of a renewable PPA contract. Basically, the value of the renewable energy production can be broken down into:

- Baseload power price (level of the forward price)

- Sustainability premium (level of the GoO price)

- Shaping costs

- Balancing costs

Baseload power price and sustainability premium

The largest value driver is the level of the baseload power price. This can be a price in the forward market or the estimated average future spot price. Furthermore, there is a premium which consumers are willing to pay if the power is proven to be green. In developed power markets, almost all generated power from larger facilities are being continuously measured and receive an electronic certificate (guarantee) of origin. The value of this GoO reflects the sustainability premium consumers are willing to pay, and is larger when the generation is local and really sustainable, e.g. with minimum impact on nature and clear skies.

Shaping costs

Unfortunately, a renewable generation asset does not produce baseload, and this leads to the shaping and balancing costs. The shaping cost is not a directly observable cost, but rather the difference between the baseload price and the realized (or effective) price in the day-ahead spot market. This difference is the combined result of a seasonal pattern (e.g. more solar in the summer), an intra-daily shape (e.g. more solar midday) and unpredictable variations due to weather fluctuations. The larger the share of wind or solar generation in the total supply, the lower are the prices at the time of production. This is the so-called cannibalization effect, leading to shaping costs. In some situations, especially reservoir-hydro production, the renewable energy production is demand following, meaning that the shaping cost is a premium.

Balancing costs

The second cost component, balancing cost, results from the intermittent nature of solar and especially from wind: their production cannot be forecast day-ahead with full accuracy. The variations between the actual production and the day-ahead forecasts lead to imbalances. Most of the time, those imbalances will be correlated with the general market imbalances, and therefore constitute a system cost, which the contributor pays for in the form of imbalance charges. On the one hand, ever-improving forecasting technologies reduce balancing costs, but the increasing penetration levels of solar and wind on the other hand raise balancing costs.

A physical renewable PPA contract which is “pay-as-produced” means that the off-taker takes care of all the volume management, including the shaping and balancing. A physical PPA contract which is “pay-as-forecast” means that the off-taker receives the day-ahead forecast power; a power trader or utility manages the short-term balancing. Finally, a physical PPA contract might have a volume which is fixed, either baseload or following some predetermined pattern; in that case, a power trader or utility (sleeve) manages both the shaping and the balancing. Because in this latter case the utility performs both the balancing and the shaping, the sleeving fee is higher.

The value breakdown shows that it is far too simplistic to state that the value of renewable power equals the baseload power price times the total generation volume. The “real value”, for the consumer and society can be much lower, due to the fluctuations and forecasting inaccuracies of the actual generation. In the following articles, we investigate this in more detail.

Feedback on our “Financials of renewable Power and PPAs”

We write the articles to share our knowledge and hope it provides a useful source of information for newcomers and experienced professionals alike. Each article will be a mix of qualitative description, some mathematical formulations and numerical examples. Whether you are buying electricity for your company, developing new projects, working for a utility, providing financing, drafting policies, or just generally interested: we hope you read the articles with interest and share your feedback with us: info@kyos.com.

KYOS puts a lot of effort to find the right balance between offering a robust deal capture system and a fully flexible spreadsheet solution. We include standard PPA pricing mechanisms for certain countries and technologies. You can find more information on our different modules for renewable PPA valuation on our renewables page.

To view this article in pdf format: PPA Contract structures and valuation – the financials of renewable power and PPA contracts

[1] In 2008 Google purchased the KYOS Monte Carlo simulation software to assess the earnings and risk distributions of its energy contracts and assets.